Let’s set the scene: it’s August of 1963 in Washington, D.C. You are only one of 200,000 demonstrators who have made their way to the Lincoln Monument in the March On Washington to demand better jobs, freedom and justice from a nation that was built on the backs of your ancestors. You are only one of millions of people of color who were forced to face inhumane conditions and found themselves spurred into a fight for a better future. One representation of a people who are hellbent on survival, equal access and pacification.

Yet, you are one — one voice that can alter the mindsets of thousands, even millions. One perspective that is so powerful, so incredibly compelling that it cannot be denied, not even by even those suffering from cognitive dissonance and with hearts stained by bigotry and hate. Imagine at that moment, knowing that your assertion of the most basic of human rights and demand for justice will pave the way for the abused and the distressed people through the nation. What would you do with that power?

The Civil Rights Movement, which ran from 1954 to 1968, sparked the flame of the Black Power Movement, which introduced us to the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the Black Arts Movement. While it is known that the BPP was dissolved by the government in 1982, some would say that the movement has never stopped. However, it has been slowed in progression by the killings of prominent figures who were in support of the cause, along with the rise of mass incarceration that extracted the Black man from the Black home, and the countless number of communities broken by the crippling effect of a long-term drug epidemic.

Despite the setbacks, the love of Black people by Black people along with art inspired by the stories of Black people remains unsuppressed and has even grown to become a prominent practice of today. A theory may suggest that we are in the second wave of the Black Power Movement in this country — Black Power Movement 2.0? Regardless, it is in this time that we are reminded of the political fights that our elders put up against the system and in turn, should find inspiration in their collective effort to eradicate inequality.

I found myself inspired in such a way after having the pleasure to experience the Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power exhibit currently installed at the Brooklyn Museum in New York (until February 3, 2019). I was able to witness the conditions of the post-Civil Rights era through the eyes of key artists such as Emory Douglas, Carolyn Lawrence, Norman Lewis and Betye Saar, as they responded to an impassioned call for Black unity by revered Civil Rights leaders while confronting and even provoking the current state of America.

I carefully digested each piece to get a full sense of the connections that laid behind them. I was caught in a rapture as if I had traveled through time to urban America circa 1975 and observed the cultural climate for myself.

More than 150 works of art are delivered in a variety of mediums including paintings, sculptures, political posters, photographs, collages and prints that are spread out between two floors. The curators arranged the show in such a way that shines a light on the communities that played a key role in the Black Art Movement — Harlem, Oakland, Watts and Chicago.

This setup also ensures to highlight the most active artist collectives at the time such as the Spiral Group (NYC), The African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists or AfriCOBRA (Chicago), The LA Assemblage (LA), just to name a few. Each group brought a different approach and aesthetic to the movement but all had the same underlying goal: to inspire and move the nation in a direction that would bring equal rights and opportunity to every man and woman.

This arrangement encourages the observer to be cognizant of this revolutionary call that rang from all corners of the country. A song of anger, dissatisfaction, alliance and power that demanded political development as it swayed to the rhythm of resilience and pride.

What I loved most about this exhibit is the clear evocation of a collective consciousness between each artist group. And, needless to say, the pieces were just as breathtaking. Without giving too much away, I wanted to share a few pieces that I found especially captivating.

Painting: Wadsworth Jarrell

Wadsworth Jarrell's Black Prince (1971) is a colorful portrait of Malcolm X composed of the letters used in one of his speeches. The text reads "I believe in anything necessary to correct unjust conditions. Political, economic, social, physical, anything necessary as long as it gets results." The AfriCOBRA painter depicted X with a raised hand and an extended pointer finger clearly portraying the revolutionary fighter's demand for change in America.

Painting: Archibald J. Motley Jr.

This piece by Archibald J. Motley Jr. is entitled The First One Hundred Years: He Amongst You Who is Without Sin Shall Cast the First Stone: Forgive Them Father For They Know Not What They Do (c. 1963). Out of all of the pieces in the exhibit, this one took me the longest to digest — I was forced to diligently interpret the layers of arduous realities that left me feeling a complexity of emotions ranging from anger to cautious optimism. Though many of the pieces had this effect on me, this one stands out entirely. In this piece, the artist narrates the history of Black suffering in early-America by setting the scene in somber hues of blue over a sable canvas. He then introduces blood-tone reds in the form of Confederate flags and burning crosses to represent the pain that was endured in those times. It truly puts you in a mood.

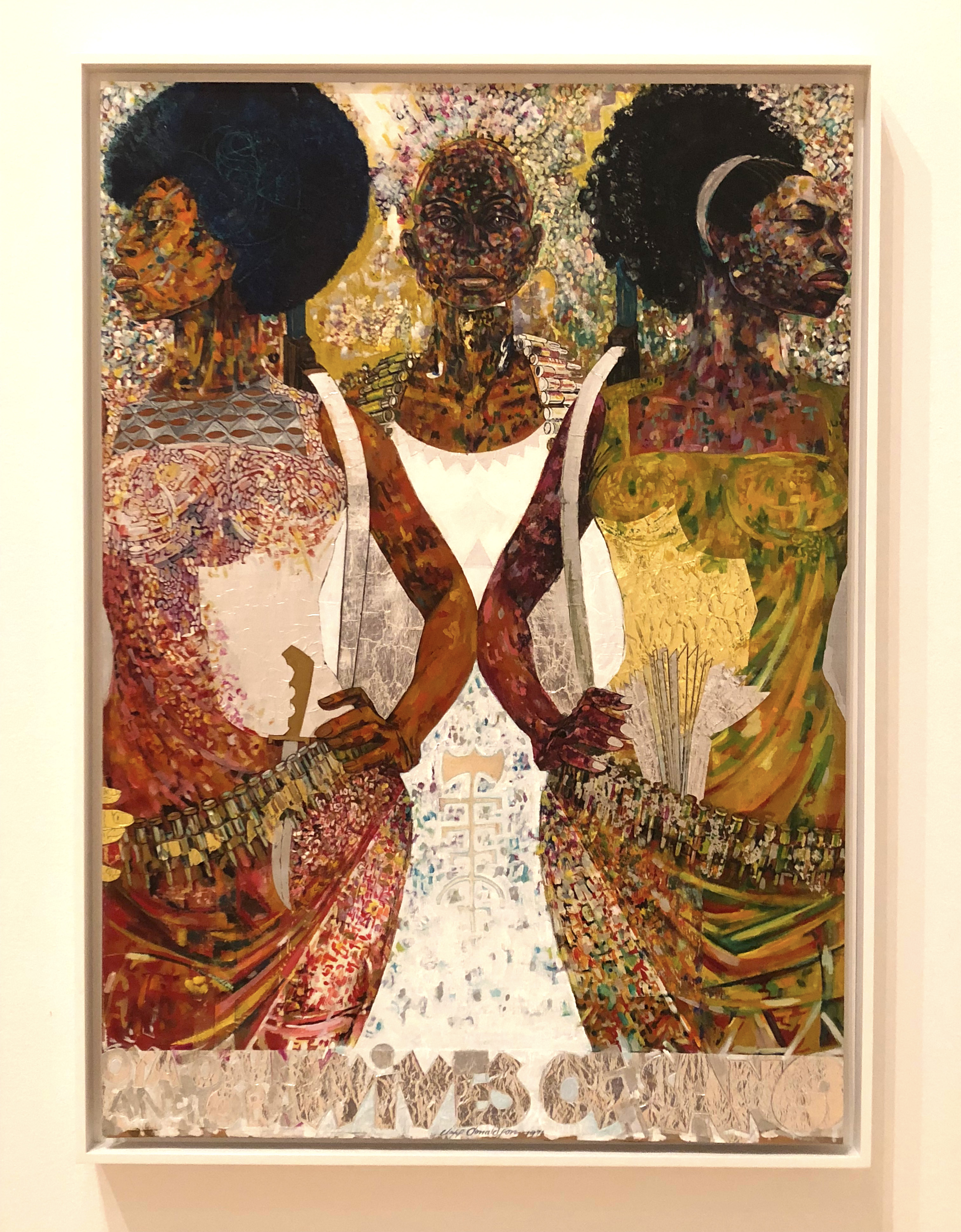

Painting: Jeff Donaldson

Jeff Donaldson's Wives of Sango (1969) screams Black Women Empowerment. In a time where many literary and art pieces focused heavily on the struggles of Black men especially, having a piece that not only represents the struggle of the Black woman but also the resilient nature of her being is profound. The painting recounts the story of Sango, the Oyo deity of Thunder who once lived as a ruler and magician in an East African Kingdom. These three women were Oba (his first wife), Oshun (Orisha of the River) and Oya (his concubine). They are portrayed as being unified and strong, wearing their natural tresses while draped in traditional garb, and equipped with rifles and army knives in a way to shed light on the Black woman's unshackling from the system. In a way, this painting embodies the stalwartness of Black women that this time period wanted to reject, which is what makes it special.

At one point, I took a moment to look away from the art to observe my surroundings, I could see on the faces of my sisters and brothers an emotion that had been charged by the underlying meanings of each piece. Emotions that are in direct correlation with the suffering of our ancestors, whose memories lie within our DNA. I think that we all felt the heavy weight of responsibility to keep the revolution going as we are still living in times of systematic racism.

As you move throughout the exhibit, you experience both pain and healing, happiness and rage, elemental fear and a deep sense of a God-given freedom despite the conditions of the time. Sentiments that are strong enough to galvanize you into action in an effort to bring about change. At this moment, I began to ask myself: what is it that we must do as a people to uplift and protect ourselves from the cruelties of this nation? How can we put an end to the killing of our men at the hand of a tempered police force? How can we demand that they hear our call for the most basic of human rights?

How is it that, after decades of fighting for equality in this country, we still find ourselves romanticizing about a time where our country loves us as much as they love our culture? What is it that we have not already done in this war against oppression?

How do we abolish mass incarceration? Rectify our internal conflicts, rebuild our communities and establish a system of recycling the Black dollar? What can we do to safeguard our financial achievements and never again have to watch it burn to the ground? When will we no longer have to censor our truest self for the comfort of whites in America?

If art was meant to do one thing, is it not to inspire you?

Ready. Set. Boss. Our daily email is pouring out inspiration with the latest #BlackGirlBossUp moments, tips on hair, beauty and lifestyle to get you on track to a better you! Sign up today.